Choosing the right fabric/textile material bring a sketched design to life. It is the basic thing a designer must initially analyse. the correct textile material defines a garment/apparel’s drape, comfort, suitability, durability, ability to incorporate elements like patchwork, embroidery etc. Apart from this, it also helps us analyse its aftercare and launderability (washability). the correct choice of fabric also helps in understanding the season in which a garment can be worn. From the first pencil stroke on a sketchpad to the final stitch on a runway-ready piece, fabric is the soul of fashion.

As per the author's experience in teaching, evaluation of budding designers and interactions with other designer's world over, it was observed that the designers usually design a garment but are unable to select the perfect fabric to execute their collection. This turns into a huge disaster most of the times and even leads to downfall of their brands/couture house.

So, as a designer it is a must to know the basic knowhow of fabrics first and then land up designing a garment or a collection.

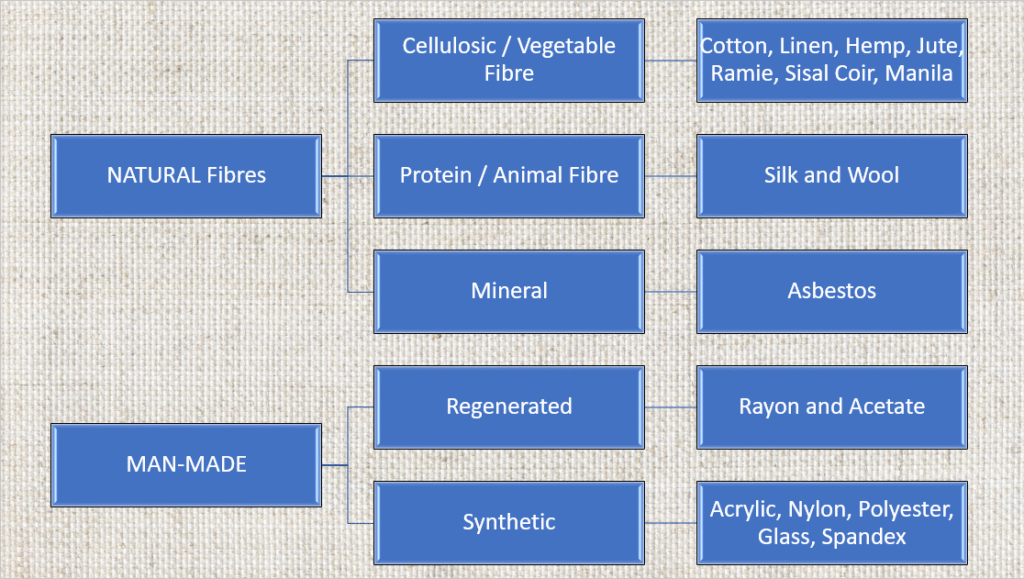

Going ahead and understanding the basic knowhows of a textile material, fabric is a sheet of fibres combined together by interloping, interlacing or bonding the fibres together. A fabric’s basic raw material is a fibre. Fibres used in manufacturing of textile fabrics, are either Natural in origin, or Manmade, or they can also be a combination of both natural and manmade fibres called Regenerated Fibres. Let’s dig a little deeper to understand how we decide on what kind of fabric to choose for what type of garment.

Natural Fibres are the ones, that we obtain from nature. Nature implies plants, animals and minerals.

- Plant fibres are obtained from stem, leaves, bark, fruit etc.

- Animal fibres are obtained from skin, hair, or secretions by the animals

- Mineral fibres are obtained from mineral deposits in the earth

The fibres available in the market from any of these sources are tested for their strength, pliability, durability, flexibility, texture, absorbency or moisture retention before being made or constructed into a fabric. they should have ample of strength, durability, pliability and flexibility to be made into a fashion garment/apparel. the texture should be such that it shouldn’t harm the skin, rather protect it from external factors like, cold, heat, wind, snow, ice, rain, dust etc. For comfort and climatic conditions, it should have the ability to absorb moisture. When we perspire/sweat, the sweat needs to be absorbed well by the fabric, to prevent any skin infection or allergenic reactions.

Qualities of Natural Fibres

- Natural fibers in general are hypoallergenic, extremely good for the skin and have high water absorbency.

- All cellulosic natural fibers can be given a tumble wash, until any dye or print is applied to it. these fibres gain almost double the strength in wet conditions, hence in day-to-day life, you may have observed that washing and wringing of cotton, linen etc. (the summer wear fabric) never destroys or damages the fabric.

- All Protein fabrics need to be dry cleaned as tumble wash or washing and wringing reduces their strength, makes the weak and prone to damages very quickly. They are wonderful fabrics for winterwear as their natural property is to trap and hold the body heat.

Man made fibres on the other hand are of two types:

- Regenerated: The ones which are made by mixing a natural fiber with a chemical in which it dissolves and is then made into a fabric eg Rayon and Acetate

- Synthetic fibres: The ones that are made by combining two or more different chemicals and then made into a fabric eg: Acrylic, Nylon, Polyester, Glass, Spandex/Lycra

These are called man-made fibres as they are manufactured in chemical laboratories or plants by mixing chemical compound that on cooling, solidify into fibres or yarns and are eventually made into fabrics.

Qualities of Man- Made Fibres

- All man-made fibres get weak when wet.

- All regenerated fibres like Rayon, Viscose, Tencel, Lyocell etc. absorb moisture, but less than the natural fibers and are mostly suitable for summer wear, during rainy season or in pleasant weather conditions. It is advised not to use them as undergarments or as lingerie wear as they can cause allergies or skin irritation.

- All synthetic fibers like Polyester, Nylon, Spandex etc. are hydrophobic and do not absorb much water. they are therefore used for making swimwear, fishing nets, winter wear jackets, as paddings for quilted garments, winter quilts etc.

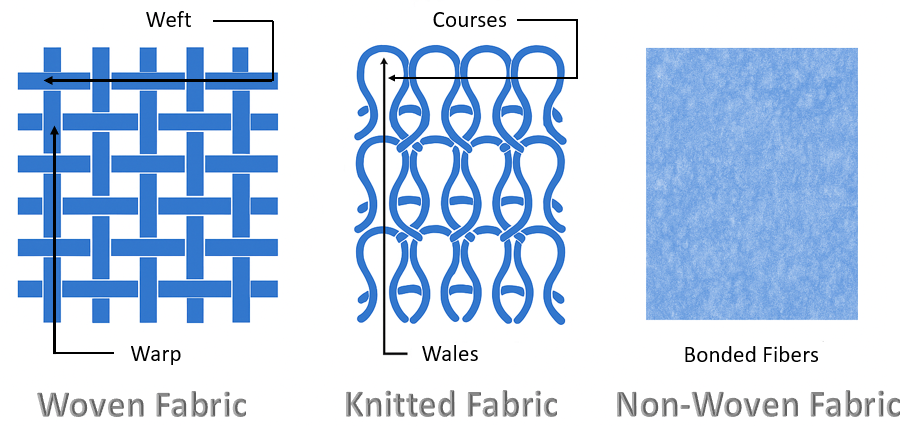

The fibres obtained from above sources, are made into yarns, the long strands of fibres combined together by the process of spinning. These yarns can be made thick or thin depending on the fabric to be constructed. For example, georgette needs a thin yarn for construction whereas denim needs a thick yarn. The thickness or thinness of a yarn determines the weight of a fabric called GSM (Gram per square meter). Higher the GSM, heavier the fabric, lesser the GSM, lighter the fabric. Another factor is the thread count of a fabric. To understand the basics of thread count, it’s important to know the types of fabric and how each one is made. There are 3 ways to construct fabrics – interlacing, interloping and bonding the fibres together.

- WOVEN FABRICS: Made by interlacing two sets of yarns, the lengthwise ones known as WARP and width wise, WEFT yarns at an angle of 90 degrees

- KNITTED FABRICS: Made by interloping minimum one set of yarn. It has loops running in lengthwise direction, known as WALES and other in width wise direction, known as COURSES.

- NON-WOVEN FABRICS: Made by bonding or entangling fibres with one another.

THREAD COUNT

Thread count can be calculated for woven fabrics by evaluating the number of yarns per square inch of a woven fabric. It is calculated by summing up the number of warp and weft yarns per inch of a woven fabric of any type or origin. For example, in a fabric if there are 133 warp yarns and 100 weft yarns, the thread count of that fabric will be 133+100 = 233TC.

The fabrics can be made using any fibres, may they be natural or manmade. Thread counts are mostly mentioned on the, commercially on home furnishing fabrics like bedsheets, table covers, table mats, throws etc., but they are essential even while selecting fabrics for designing garments. While going out purchasing fabrics one can enquire for the thread count to match with their designed collection.

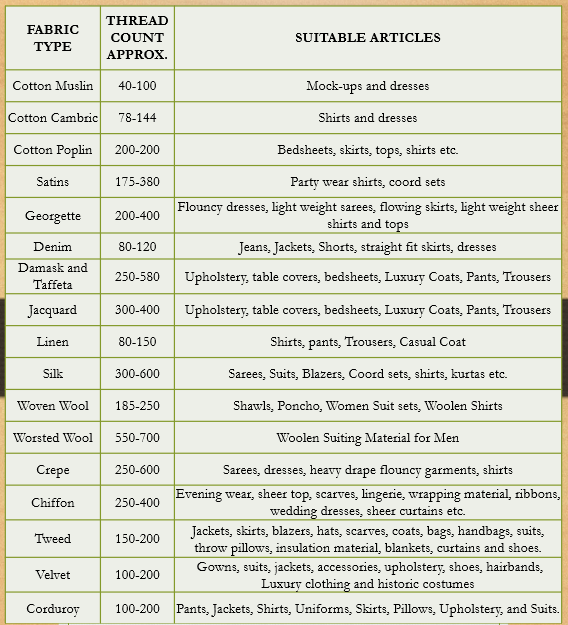

Mentioned here are some of the majorly used fabrics and their approximate average Thread count, available commercially

But it must be noted that it is not the only parameter that determines the quality of a fabric. The other factors are

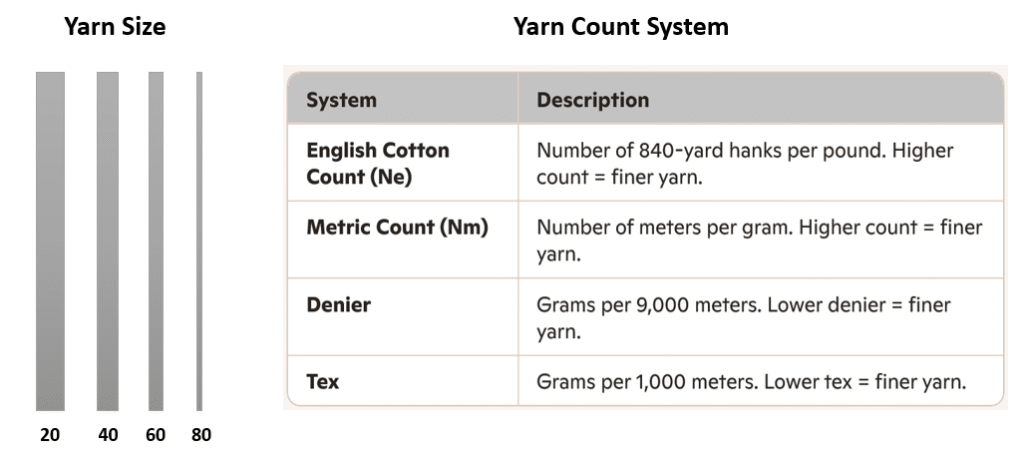

- YARN SIZE – It determines the weight of a fabric, higher the yarn size, lighter the fabric. It is measured in two systems, namely Yarn Count System (It measures the length per unit weight of yarn) and Yarn Weight Category. The yarn count system is majorly used by fashion and textile industry and is measured in the unit Ne. So, a 50 Ne cotton yarn is finer than a 10 Ne yarn.

- YARN QUALITY – It determines the longevity of the fabric. The better the origin, the longer will be the life of a fabric.

- WEAVE – The more compact the weave, higher will be the thread count, more will be the strength and tougher will be the drape of the fabric.

Want to know more about Weaving, Knitting, Non-Wovens, Fabrics, Yarns or Fibres? Comment below